In the history of automotive design, a few creations do more than capture attention—they redefine the visual and conceptual foundations of the industry. The Lamborghini Countach is one of these rare works. When it appeared as a prototype at the 1971 Geneva Motor Show, it didn’t simply introduce a new model; it detonated existing conventions. Half a century later, it remains one of the purest case studies of how a single theme, when pursued without compromise, can transform design language.

The Countach’s story, however, does not begin with that show car. Its roots trace back to a young Marcello Gandini at Bertone—a designer determined to escape the gravitational pull of curves and decorative cues that dominated the 1960s. Gandini’s vision was unambiguous: cars were machines, and machines deserved to look engineered, not ornamental. He wanted to replace sensuality with geometric clarity, to craft forms that expressed structural intent rather than romantic gestures. This philosophy found its first public voice in a pair of audacious concepts.

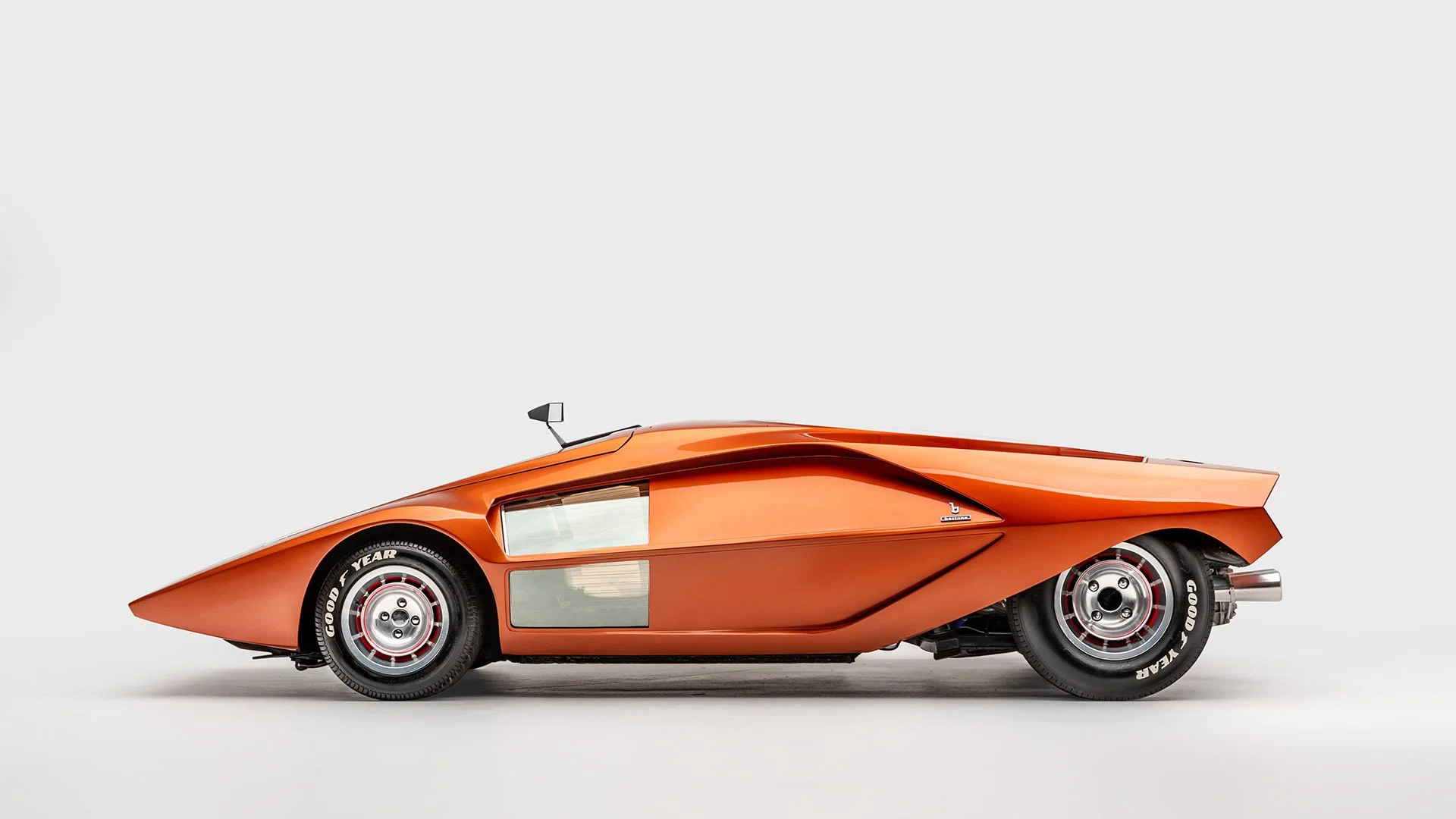

In 1968, Gandini presented the Alfa Romeo Carabo, the first true articulation of his wedge concept. It sat impossibly low, its prow a sharpened blade, its body a composition of taut, intersecting planes. More than a showpiece, it introduced a solution that would become Lamborghini’s signature—the scissor door, born out of necessity for ingress in tight packaging. Two years later, Gandini pushed abstraction even further with the Lancia Stratos Zero, a concept so radical it blurred the boundary between vehicle and object. With its nearly horizontal wedge and exaggerated cab-forward stance, it looked like a spacecraft dropped onto four wheels. These studies weren’t isolated provocations; they were Gandini’s manifesto. The wedge wasn’t an aesthetic trend but a language of speed rendered as geometry, and the Countach would translate that language into a production reality.

The mandate from Ferruccio Lamborghini was as audacious as the designer himself. The Miura was already considered an apex of automotive beauty, yet Ferruccio didn’t want refinement—he wanted rupture. He wanted a car that would silence a motor show floor and make Ferrari look old. There was no formal brief, only a demand for shock value. Engineering decisions added complexity and opportunity: chief engineer Paolo Stanzani’s plan to mount the V12 longitudinally behind the driver changed everything. This wasn’t just a mechanical shift; it redrew the blueprint for the car’s architecture, stretching the wheelbase, altering weight distribution, and forcing a rethink of cabin placement. For Gandini, this architecture became the sculptural foundation for something that felt extraterrestrial.

Great design begins with proportion, and Gandini’s mastery of this principle remains one of the Countach’s most enduring lessons. The car stood just 1.07 meters tall—a dimension that did more than lower the roofline; it recalibrated the car’s stance. By pushing the cabin forward toward the front axle, Gandini exaggerated the endless deck over the engine, turning mechanical packaging into visual theater. From a side profile, the Countach resolves into a near-perfect triangle, its apex thrusting toward the horizon like an arrowhead. Even at rest, it communicates acceleration. For designers, this remains a benchmark: proportion isn’t an afterthought—it is the essence of identity.

If the Miura was sculpture, the Countach was architecture. Gandini eliminated ornamental transitions, opting instead for a disciplined composition of planes. The hood wasn’t a shape—it was a structural slab, angled downward with mathematical intent. The flanks were broad, flat surfaces punctuated only by calculated incisions for cooling and aero management. Edges were crisp, their intersections precise, creating an object defined not by softness but by tension. This tension is what gives the Countach its enduring vitality. Every breakline, every shadow, feels earned rather than decorative.

Among its many innovations, none symbolized Gandini’s philosophy more than the scissor door. Originally tested on the Carabo, this vertical pivot was born from necessity: the Countach’s wide sills rendered conventional doors impractical. Yet in Gandini’s hands, a packaging constraint became an icon of brand identity. The act of opening those doors was no longer a mechanical gesture—it was a ritual. For car designers, this remains an eternal lesson: true design excellence transforms functional solutions into emotive experiences.

Look closer and the Countach reveals Gandini’s genius in surface transitions. Where many designers would have softened the junction between hood and fender, Gandini draws a line of incision, preserving clarity. The tumblehome is nearly absent, reinforcing the monolithic wedge profile. Even the rear haunches, which on other cars might swell with organic sensuality, are disciplined slabs fractured by the surgical cut of air intakes. These cuts do not appear apologetic—they appear intentional, amplifying rather than compromising the theme. At a time when curvature equaled desirability, Gandini’s refusal of softness felt almost confrontational.

Then came the engineering ballet. The longitudinal V12 was a masterpiece of ambition but a challenge in heat management. Cooling demands introduced elements that could have destabilized the form: NACA ducts, gaping side intakes, and later exaggerated arches. Yet instead of burying these solutions, Gandini elevated them, integrating them into the car’s rhythm until they became signatures. Over time, performance upgrades and regulations added layers—wheel arch extensions, wings, spoilers. Some lamented the drift from the prototype’s purity, yet the Countach absorbed this complexity without forfeiting its stance or its essence. This adaptability speaks to the strength of its core gesture: when the theme is clear, it survives evolution.

When the LP500 prototype rotated under Geneva’s lights, the silence was deafening before the applause erupted. A mechanic whispered a Piedmontese expression of astonishment—“Countach!”—a word that became the car’s name because nothing else could capture its shock value. For journalists, it was a headline. For designers, it was a reset button. The Countach didn’t look modern—it made everything else look obsolete. It obliterated the flowing idioms of the 1960s and announced a new order defined by geometry, angularity, and visual tension. The wedge era had begun, and its shockwaves would shape everything from supercars to sedans for two decades.

The production Countach endured for 16 years, mutating from the almost elemental LP400 to the theatrical 25th Anniversary edition. Along the way, it became more than a machine; it became a cultural artifact, a poster pinned on adolescent walls, a cipher for speed and excess. Yet for the design community, its legacy is deeper and more instructive. It legitimized the notion that concept-car radicalism could survive the transition to reality. It reaffirmed the primacy of proportion. It demonstrated the beauty of functional honesty—where ducts, scoops, and mechanical necessities become part of visual identity rather than blemishes to be disguised. And above all, it reminded the industry that progress is born of risk. The Countach was not safe. It was audacity in aluminum, and that audacity became history.

Half a century later, the Countach still radiates relevance because it embodies principles that outlive trends. Begin with a strong theme. Execute with precision. Celebrate function. Trust proportion over ornament. And above all, have the courage to draw the line no one else dares to draw. For car designers, the Countach is more than an icon—it is a living textbook in clarity, tension, and conviction. It proves that when vision refuses to compromise, design ceases to be a product and becomes a legend.